Lussu file #2: Wines and goblets

Should Beatrice Warde’s ‘Crystal goblet’ be seen, at best, as a harmless promotion of Monotype?

In June 2006 Progetto grafico hosted a debate on Beatrice Warde’s famous pamphlet, the Crystal goblet, together with an Italian translation of the original text that was published as a small booklet attached to the journal.

Lussu teamed up with two of his old friends, Antonio Perri and Daniele Turchi (the latter shared a studio with Lussu in Rome), and they wrote an article that includes a sharp and severe critique of Warde’s idea of typography. They explained how Warde’s metaphor is untenable from both typographic and linguistic standpoints, and how the whole idea of transparent typography, as postulated by Stanley Morison (of whom Warde was a dear friend and a keen fan) is rooted in the prejudicial idea that writing is simply the transcription of speech.

Lussu and his mates started from Warde’s pamphlet to discuss what they were really interested in: a new theory of writing, free from the paradoxes and contradictions of the Hegelian ‘world of texts’ that has done so much damage to visual communication.

The translation of this article was challenging, due to the semiotic and linguistic discussion in the endnotes rather than in the main text — another of Lussu’s writing habits. So we invited Robin Kinross who is an old friend of Lussu’s to edit the translation. Kinross shares an interest in such matters with Lussu and in 2006 he was invited to contribute to the same issue of Progetto grafico with another critical article. In this he suggests a different theory of typography in contrast with the idea of transparent typography.

Finally we asked James Mosley his opinion on the Crystal goblet and he kindly wrote a brief note for us on Warde’s archaic terms that we include below following Lussu’s text.

Giovanni Lussu: Wines and goblets

Written with Antonio Perri and Daniele Turchi.

Excerpt from Progetto grafico 8 (June 2006, pp. 182–187). English version edited by Robin Kinross.

1. There is no doubt that Beatrice Warde was a very significant figure in twentieth-century typography. To start with, she was the first woman of importance in the history of the field, before Zuzana Licko or Carol Twombly, or Nelly Gable, who now cuts punches, as far as we know the first ever by a woman, at the Imprimerie Nationale in Paris. One of us is personally in Warde’s debt for enabling him to start his own career in typography, in the mid-1960s, using the Monotype student leaflets, those excellent introductions to typography that Warde produced during her many years as publicity manager of the legendary English firm. One of her essays, recently re-published, on the choice of type, is still admirable for its expertise, passion and clarity [1]. A formidable woman, certainly, but also a rather nice one. Her relationship with Eric Gill has left us with some good portraits of her [fig. 1].

2. But what is the Crystal goblet? We need to look at the circumstances surrounding this piece of writing, in 1932, and we should remember first of all that Beatrice Warde, while already having a well-established culture in printing before they met, was an enthusiastic follower of her mentor Stanley Morison, who in 1930 publicised the dogma of ‘invisible type’: ‘Therefore, any disposition of printing material which, whatever the intention, has the effect of coming between author and reader is wrong’ [2] [fig. 2]. Warde was also addressing an audience of craftsmen (the British Typographers Guild) in her capacity as publicity manager of the Monotype Corporation: in other words she was there selling machines and type that day at the St Bride Institute in London. We should also bear in mind the underlying, obstinate mistrust of a very traditionalist profession towards the annoying, uneducated modernism of continental Europe (Lissitzky, Tschichold, Bayer, Moholy-Nagy and company).

3. What is the point of this elegant metaphor, except to show off Warde’s undoubted narrative and entertainment abilities? How do typography and text relate to the rhetorical conceits of crystal and wine? Of course this milieu of down-to-earth artisans would not have been familiar with Peirce or Saussure, nor would they have had animated discussions about Louis Hjelmslev’s Principes de grammaire générale, and indeed why should they? [3]. The problem is that, even on the basis of day-to-day common sense, it is difficult to give a full account of the meaning of Warde’s fable.

4. We can assume that, given their prevailing interests, Morison and Warde were referring exclusively to typography in books. To take just one example, it is hard to relate the arguments of the Crystal goblet, however we choose to take them, to the Gollancz dust-covers designed by Morison himself, who apparently didn’t practise what he preached [fig. 3]. How should we understand ‘transparency’ here? One sharp commentator wondered whether Chesterton and Lewis were unusually corpulent (indeed Chesterton was), and Keynes and Forster particularly slim.

5. But what type of book? To take an example from the same area (the page of a book composed in Monotype typefaces from a collection published in 1931 for promotional purposes), in a complex bibliography it is hard to see what this invisibility is that Warde talks about [fig. 4]. Indeed, it seems rather clear that in this case ‘transparency’, namely the possibility of getting quickly and surely to the ‘wine’ provided by the authors, is ensured by the fact that the typography is anything but invisible. It is the precisely the very visible differentiations that guarantee good assimilation of the text: type sizes that are different, bold, italic, small caps, composition in one or two columns. What is invisibility? Are we perhaps saying much more mundanely that things should be done with a bit of common sense?

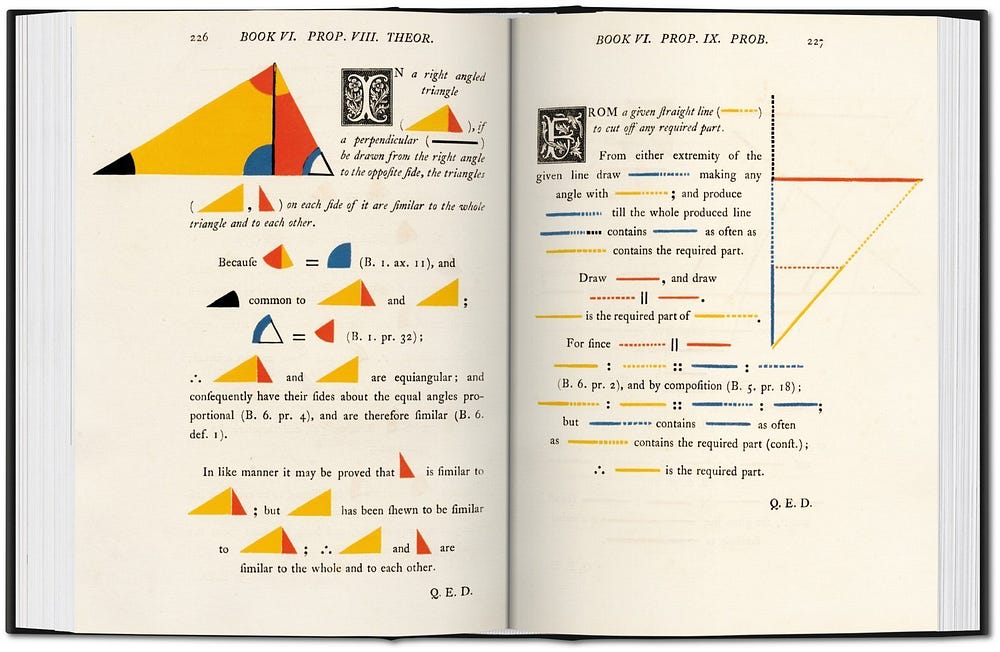

6. And books today are mostly of this intrinsically complex genre: school textbooks, legal, technical and scientific books, professional manuals, cookery books, telephone directories, catalogues, railway timetables, and so on and so forth. Not to mention books that founded so-called Western culture, beginning with the Bible itself. How could it be read without careful treatment of differences and visibility, without giving prominence to the numbering of the verses? Could we read Euclid’s Elements in the form in which it was presumably written, with no differentiation between upper and lower case letters, without punctuation marks and without highlighting of the titles? What would we do with Byrne’s [fig. 5] extraordinary, typographically very unorthodox edition? And what about Wittgenstein’s Tractatus logico-philosophicus or Baruch Spinoza’s Ethica more geometrico demonstrata, books which, like the Elements, are structured with a network of references, and whose wine could be tasted much better if the type was highly visible?

7. The Crystal goblet therefore seems to be concerned only with ‘normal’ books, preferably plain text without footnotes: nineteenth-century novels, very conventional essays, letter after letter, line after line, page after page, to be read ‘on auto-pilot’. We are back to good old common sense, or rather to the most blatant platitudes: there mustn’t be too many characters per line, the lines mustn’t be too close together, the type must be legible. But what do we mean by legible? We know that essentially, taking for granted what is necessary for good visibility (letters distinct from one another, internal spaces not closed up, etc.), the most legible types are the ones we are most used to (and nowadays the average reader is used to many more varieties than were current in 1932). And we also know that what Warde really meant and suggested, maybe out of conviction but also because of her job, was that the most legible type was Monotype type. So, given that in effect it contains nothing else, should the Crystal goblet be seen simply as an amiable and harmless promotion of Monotype?

8. A little digression. Years later, in 1959, Morison and Beatrice Warde lent plausibility and authority to the publication of a study on legibility, A psychological study of typography by Cyril Burt [4].

The samples of type on which the research was conducted were, strangely enough, provided by Monotype, and the most important finding, strangely enough, confirmed Morison’s theory that type with serifs is more readable than that without. After Burt’s death (he had been knighted for services to psychology), some researchers wanted to verify the data from his famous studies on twins. They looked for the two collaborators cited in the study, and, surprise surprise, they had never existed. Sir Cyril Burt had made it all up [5]. Needless to say the study on legibility suffered somewhat.

9. So, is the Goblet just a harmless promotion of Monotype for the typographical composition of novels? Unfortunately no, because the metaphor of the wine and the goblet does not work at all, and indeed is very misleading. Since we are talking about things which are read, and which are therefore assimilated by means of sight, it is very hard to separate the wine from the goblet, the text from its visible form. Where does the text reside, before it is composed into visible type? In what idealistic Hegelian [6] or perhaps Platonic world of texts? We are truly in the midst of the paradoxes and contradictions born out of the alphabetic and Eurocentric prejudice: the idea of writing as simply transcription of speech. It is a pity that, as has been argued by Jack Goody, Giorgio Raimondo Cardona, Roy Harris and many others, this simplistic way of not seeing writing no longer stands up [7]. Let us return to the Goblet as a general plea for typographical discretion, based certainly on shaky theoretical assumptions, but nevertheless backed up by the type and the mechanical composition procedures of the Monotype Corporation.

10. If we make a distinction between books already written and those yet to be written, there are some further worrying observations to be made. Warde’s argument is apparently more plausible if adapted to the classic novel, if we believe that War and Peace should be composed and presented more or less in the form which Tolstoy imagined while he was writing it (although some devices in the form of notes and indexes of places and people, maybe some maps and, why not, the odd diagram of relations between events would today be most welcome). We have already said that we read Euclid in a form very different from the original: fortunately things move on, and each age adapts its historical heritage to its own culture and sensibilities. And what about Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne, perhaps the most popular eighteenth-century English novel? Would Morison and Warde have moved heaven and earth to stop it being published? Not so much because of the black or marbled pages, but because of the constant typographical core, superbly visible and non-transparent (abnormal dashes in the course of the text, entire paragraphs made up of asterisks, insertion of fists and Greek and Gothic characters, unpredictable numbering of chapters and so on) [fig. 6]. And what should an author do today? To follow the reasoning of the Goblet, even though it makes no sense, would be to create a kind of self-referential short-circuit that would frustrate any attempt at experimentation, however modest.

11. What is left of the Crystal goblet? As it seems to make no sense, it remains a purely circumstantial document, of the history of the Monotype Corporation and the sociology of typography, steeped in post-Victorian conservatism. A sort of parable for simple souls, preaching the duty to stick closely to the established conventions. In 1932 they were the conventions of Monotype, today they would be the default settings of Microsoft Word. There are so many texts, widely available today [8], that go straight to the substance of typography, by Tschichold, Dwiggins, Sutnar, Goudy or Warde herself. Why re-publish the Crystal goblet? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind, the answer is blowin’ in the wind.

ENDNOTES

1. On the choice of typeface, in Texts on type. Critical writings on typography, edited by Steven Heller and Philip B. Meggs, Allworth Press, New York 2001, pp. 193–97.

2. Stanley Morison, First principles of typography, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 1967, p. 5.

3. Today it seems indeed entirely legitimate to take the arguments developed in the Crystal goblet literally, and see whether some sense can be made of it (semantically) in some possible world. In other words: What would this typography really be in a theory of communication where the one main idea, the most important thing, to quote Warde, is ‘that it conveys thought, ideas, images, from one mind to other minds’? In such communication, the dichotomy of expression/content would lose the symmetry lent to it by semiolinguistic rules. The ‘form’ (i.e. the typographic expression) becomes a simple and secondary ‘pretext’ for the transmission of ‘content’ (indeed intangible and very important): following this reasoning, expression and content are not two levels presumed to be reciprocal (as in Saussurian and later Hjelmslevian discourse) because there is in some way a given content (= idea/thought) that is, so to speak, ‘covered’ by the typographical expression. From a linguistic and semiotic point of view, however, this thesis is untenable.

4. Robin Kinross, Modern typography, Hyphen Press, London 2004, p. 136.

5. Alexander Kohn, False prophets. Fraud and error in science and medicine, Blackwell, Oxford 1986, pp. 52–57.

6. The idea of an alphabet that aspires to be ‘transparent’ to the Spirit, ‘a literal form of transmission of thought’ reminds us strangely of the Hegelian vision of writing that ‘lives’ only at the moment when it ‘dematerialises’ as such, giving access to the sound truly connected with the spiritual content: ‘printed or written letters, it is true, are also existent externally but they are only arbitrary signs for sounds and words. […] Print, on the other hand, transforms [the vitality of sound penetrated by the idea] into a mere visibility which, taken by itself, is a matter of indifference and has no longer any connection with the spiritual meaning’ (G.W.F. Hegel, Aesthetics. Lectures on fine art, Oxford, Clarendon Press 1975, p. 1036). In these statements by Hegel we find a characteristic mixture of ethnocentrism and evolutionism that are intrinsically contradictory, and from which even Warde is not immune: on the one hand alphabetical script is the most ‘intelligent’, precisely because it is subject to orality, which makes it the ‘writing of the spirit’, and, by distancing ourselves from the ‘concrete sense-perceptible’ typical of ‘hieroglyphics’ (understood as ‘dead’ signs) we focus on ‘abstract elements’ of the word ‘purifying [of] the ground of interiority within the subject’; on the other hand, however, it ‘suppresses’ the other scripts, at the same time assuming their characteristics — because habit transforms the alphabet into a kind of ideography and ‘makes it into a hieroglyphic script for us, such that in using it, we do not need to have present to our consciousness the mediation of sounds’ (Hegel, Encyclopaedia of the philosophical sciences, quoted by J. Derrida, Of grammatology, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press 1976, p. 25). The transparency of the alphabet, which, according to Warde’s allusive prose, makes possible the ‘magic’ that is ‘to transfer and receive the contents of the mind’ which are also and above all ‘images’ — is ultimately the fruit of its intrinsic phoneticity: the visual form of the script disappears from the horizon, diaphanous as the glass of the famous window …

7. The ‘literal’ interpretation of Warde is ultimately based on a paradoxical assumption, long since undermined in the context of an anthropologically oriented theory of writing: the Lockian-empiricist image of language as ‘thought transference’ from one mind to another. If it is problematic where it is applied to verbal communication, that image becomes even more problematic when applied to the written word: to consider irrelevant the material, social and publicly observable aspects of communication and to give priority to the ‘inner experience’ and ‘private thoughts’ of the writer and reader is to preclude any ‘rational’ (not ‘magical’, therefore) understanding of the communication process as an inter-subjective process — as the veiled scepticism of Locke about the realisation of a true identity of thoughts among participants in communication confirms, and as Roy Harris points out in his critique of telementational theory. In fact Warde does not take to extremes the intrinsically pragmatic idea of printing as a way of doing something — i.e. the performative role of the written word, the fact that behind the production (but also the fruition) of a printed text there is a ‘doing’ that is at the same time practical/empirical and completely anti-realist: like any kind of text, the printed word is a complex product around which the community builds various models of behaviour that lead us to believe that the individuals involved act ‘as if’ they understood — irrespective of whether something is actually ‘transferred’ from one mind to another, and also irrespective of what is transferred. For Warde, on the other hand, the ‘doing’ of typography is only the fact of being a medium-for-thoughts, and not the operative ‘make-to-doing’ that the objects of writing induce in the reader.

Why is the question of transparency so fascinating, given that as soon as you tackle it you dive into a sea of contradictions and non sequiturs. The answer in the end is not that difficult, and leads back to the Hegelian approach: the real problem that ‘transparent’ communication should find a final answer to is the idea of the unvarying quid, i.e. the pure linguistic, the content (of thought?) insensitive to the graphical-connotative differences. The point, however is another: does this ‘pure’ and ‘unaltered’ content exist apart from its visible manifestation? Harris would say it does, but unlike what a Hegelian might think we are not dealing with an original metaphysical ‘positivity’ but a ‘historical’, conventional and constructed product: the crystal goblet exists because certain reading practices have made it common for us to consider texts as typographically transparent, often on the basis of specific genres or standard typographical products. That goblet still has a form — and just as a red wine glass cannot be identical to a prosecco glass, so our expectations about the typographical form of particular texts make us feel it so consubstantial to the quid that constitutes its contents that it becomes, indeed, invisible. It is therefore possible that violation of the general typographical rules is no longer perceived as such, when the text has now been introjected by a culture through a visual-typographical ‘degree zero’, regardless of philological, typographical or exquisitely aesthetic considerations. But the road of conscious, intended violation is still open, one that ‘restructures’ the text depending on its peculiar way of being made visible, and therefore precludes from the outset the possibility of ‘extracting’ all the quid from it because the quid is identified, precisely, with the graphic manifestation. The Futurist works belong to this genre, of course, but so do masterpieces like Tristram Shandy [fig. 6] and a myriad of avant-garde texts, experimental graphics and so on. There are, however, some really very interesting cases where it seems that the unvarying textual quid is not linguistic (verbal or mental), but in a sense assumes a more abstract and ‘universally human’ consistency, logical in nature — as in the case of Euclid’s Elements [fig. 5], a typographical form which though undoubtedly transparent is not anchored in a linguistic dimension but has logical-relational functions and articulations. It is worth asking whether this is not after all the road that the typography of the future could (should) take: alongside the mainstream of consolidated textuality, alongside creative experimentalism, there is room for reflection on the graphic elaboration of information finally freed from Hegelian or aestheticising prejudices, and where the linearity of linguistic syntax never exhausts the communicative potential of the text, which will rather be a finishing of the disposition of graphic traits (internal entax), figures and sets of figures (external entax) within an area of inscription with a relatively autonomous planar and synoptic dimension. All this, of course, means we must continue to reflect on ways in which the non-linear dimension of entax conditions the reading and usability of any text. If it is true that not all graphic/writing or notational traditions have developed that flattening of entax on syntax which — according to the normative view of the Graeco-Latin tradition — should characterise the relationship between speech and writing in the case of the alphabet, then in the future we may be able to dispel once and for all the ‘myth’ of invisibility so cleverly formulated by Beatrice Warde: ‘Type well used is invisible [how? if it is precisely its visible entax that makes communication possible!], just as the perfect talking voice is the unnoticed vehicle for the transmission of words, ideas [never mind the importance of the ‘grain of the voice” on which Roland Barthes insisted so much].’

8. In addition to the already cited Texts on type, edited by Heller and Meggs: Typographers on type, edited by Ruari McLean, Lund Humphries, London 1995; Looking closer 3: classic writings on graphic design, edited by Steven Heller and Rick Poynor, Allworth Press, New York 1999; Graphic design & reading: explorations of an uneasy relationship, edited by Gunnar Swanson, Allworth Press, New York 2000.

The text of Beatrice Warde and its archaisms

A side note by James Mosley on the Crystal goblet

Imagine that you have before you a flagon of wine. You may choose your own favorite vintage for this imaginary demonstration, so that it be a deep shimmering crimson in color. You have two goblets before you. One is of solid gold, wrought in the most exquisite patterns. The other is of crystal-clear glass, thin as a bubble, and as transparent. Pour and drink; and according to your choice of goblet, I shall know whether or not you are a connoisseur of wine.

These terms are all deliberately and self-consciously archaic or ‘poetic’: I have followed them with normal modern English ones.

flagon = bottle

vintage = kind of wine

so that it be In modern English one would not use a subjunctive here, but say ‘so long as it is’. (And why this dismissal of white wines, which often have a characteristic and delicate colour of their own?)

crimson = red

goblets = glasses

wrought = made

Notice that there is not one word by Warde about choosing a shape of glass that captures and enhances the ‘nose’ or the smell of the wine, a feature which is emphasised in most modern writing about the choice of wine glasses.

‘Crystal-clear’ is not in itself an archaic term, but borders on it: ‘clear’ would do just as well. The term ‘crystal’ is normally used for the naturally solid and often transparent form of any mineral: here its use is just another archaism or pretentiously ‘poetic’ term.

Wine makes you drunk and confuses your judgement. There is not a hint of this from Warde, but I can’t help wondering if she wrote this paragraph after having had a few glasses.